“A genealogy for feminist sf [science fiction] would not constitute a chart depicting direct lineages but would offer us an ever-shifting, fluid mosaic, the individual tiles of which we will probably only ever partially access.”–L. Timmel Duchamp

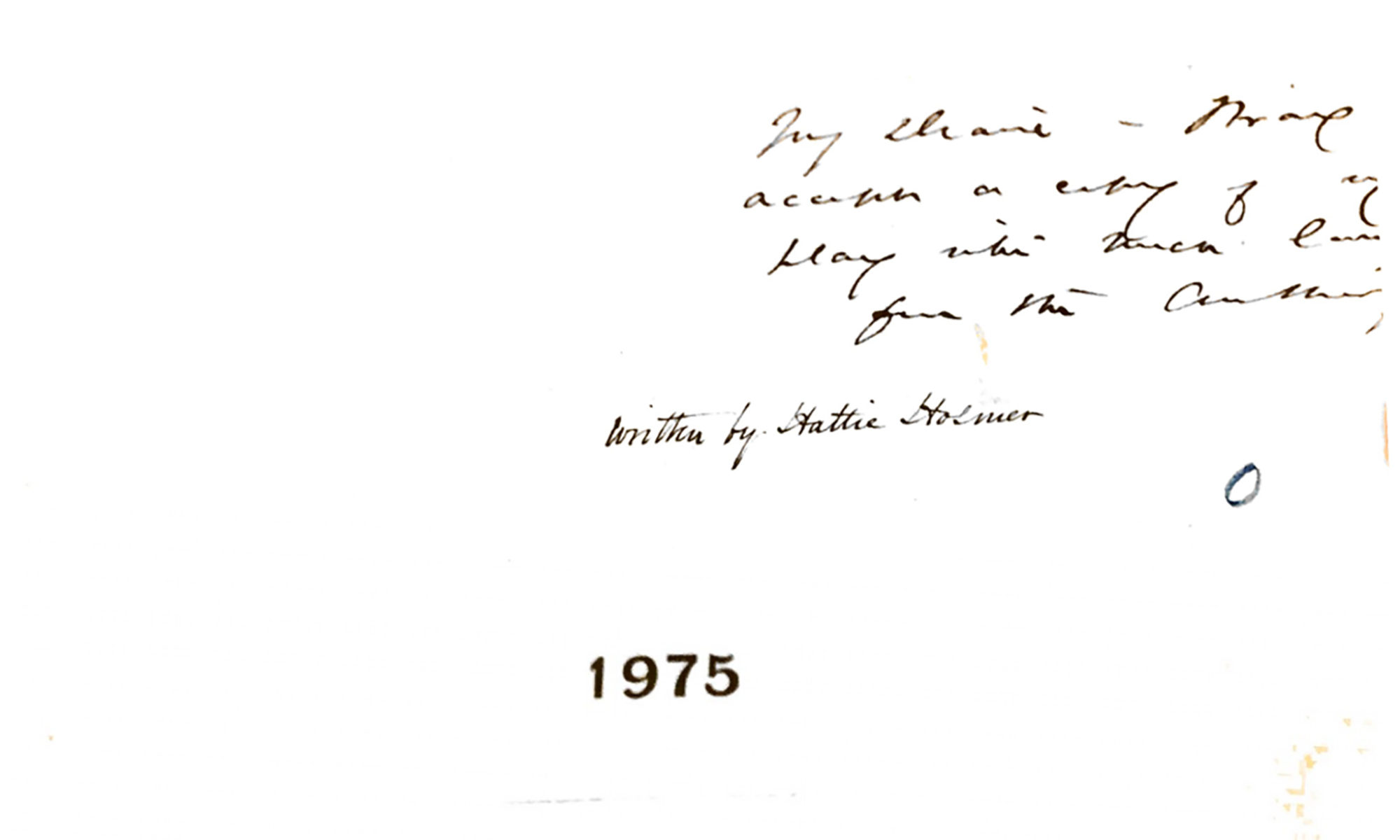

Explaining her inspiration for 1975, Harriet Hosmer exclaimed, “The ghost of Shakespeare came to my aid.” She thus presented the play as coming to her complete, out of the ether in a brilliant moment of inspiration. In fact, she wrote within a tradition of American and British women using time travel in science fiction and utopian fiction as a way to envision worlds where women have political power and opportunities in the public sphere and to question assumptions about women’s “nature.” Other authors depict utopias below the earth’s surface or on other planets. As Alessa Johns explains, in feminist utopias “Characters move beyond their world, often through time-travel, in order to effect present and future change” (187). In works such as Mary Griffith’s Three Hundred Years Hence (1836), Betsey Chamberlain’s “A New Society” (1841), Jane Sophia Appleton’s “Sequel to the Vision of Bangor in the Twentieth Century” (1848), Elizabeth B Corbet’s New Amazonia: A Foretaste of the Future (1889) and Winifred Harper Cooley’s A Dream of the 21st Century (1902) characters travel in time—or dream of traveling in time—to find worlds in which women have gained political rights or more cultural power. Annie Denton Cridge’s “Man’s Rights; or, How Would you Like It?” (1870), Elizabeth Corbett’s “My Visit to Utopia” (1869), Mary Bradley Lane’s Mizora (1880-1881), and Alice Jones and Ella Merchant in Unveiling a Parallel (1893), are not time travel narratives, but they do include characters who dream of or visit societies in which women have more opportunities than their authors found in their own time and place.

Hosmer never stated that she read or even knew of science or utopian fiction, but, tellingly, two of her earliest boosters were also among these authors of these works. In 1846, Lydia Maria Child published “Hilda Silfverling,” in which a woman wrongly accused of infanticide in 1740 is put into a cryogenic sleep and wakes up 100 years later. Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s 1838 poem “An Island” depicts her dreaming of a “pastoral earthly paradise where women co-exist happily with nature, free of the tyranny of men,” before waking. Given her close connections to the authors it is likely Hosmer knew of the earlier works by Child and Browning. Long ignored or written off as a somewhat embarrassing quirk in Hosmer’s biography, the play forms part of a tradition—a tile in the mosaic–of female authors using science fiction to challenge assumptions about women in their societies and dream of a different world.

Sources for 19th-Century Time Travel Science Fiction by British and American Women

- Ashley, Mike, ed. The Dreaming Sex: Early Tales of Scientific Imagination by Women. Peter Owen Publishers, 2011.

- Ashley, Mike, ed.. The Feminine Future: Early Science Fiction by Women Writers. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2015.

- Bradley, Mary. Mizora, a World of Women. Introduction by Joan Saberhagen. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

- Daly, Liz. “Utopian-Novels.” GitHub, 2019.

- Kessler, Carol Farley. Daring to Dream: Utopian Fiction by United States Women Before 1950. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1995.

- Jones, Alice and Ella Merchant. Unveiling a Parallel: A Romance. Ed. Carol A. Kolmerten. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse UP, 1991.

- Ockerbloom, Mary Mark. “Pre-1950 Utopias and Science Fiction by Women: An Annotated Reading List of Online Additions.” A Celebration of Women Writers. University of Pennsylvania, 2019.

Scholarship on 19th-Century Time Travel Science Fiction and Utopian Fiction by Women

- Beaumont, Matthew. “‘A Little Political World of My Own’: The New Woman, the New Life, and ‘New Amazonia.’” Victorian Literature and Culture. 35, no. 1 (2007): 215-232.

- Broad, Katherine. “Race, Reproduction, and the Failures of Feminism in Mary Bradley’s Mizora.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature. 28.2 (Fall 2009): 247-266.

- Cranny-Francis, Anne. Feminist Fiction: Feminist Uses of Generic Fiction. Cambridge: Polity, 1990.

- Culkin, Kate. “Prophetic Dramas: The Time Travel Narratives of Harriet Hosmer and Frances Power Cobbe.” In Neglected American Women Writers of the Long Nineteenth Century, edited by Verena Laschinger and Sirpa Salenius. New York: Routledge, 2019: 158-172.

- Daly, Liz. “Her Stories: Fictional Utopias of 19th-Century Women.” Medium. Feb. 20, 2018.

- Donawerth, Jane and Carol Kolmerten. Utopian and Science Fiction by Women: Worlds of Difference. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University. Press, 1994.

- Duchamp, L. Timell. “Reflections on Women, Feminism, and Science Fiction, 1818-1960: For a Feminist Genealogy of Science Fiction.” Foundation: The International Review of Science Fiction. 31.84 (Spring 2002): 49-58.

- Hopkins, Lisa. “Jane C. Loudon’s ‘The Mummy!’: Mary Shelley Meets George Orwell and They Go to in a Balloon to Egypt.” Cardiff Corvey: Reading the Romantic Text. 10 (June 2003): 5-16.

- Karcher, Carolyn. “Patriarchal Society and Matriarchal Family in Irving ’s Rip Van Winkle and Child’s “Hilda Silfverling.” Legacy. 2.2 (Fall 1985): 31-44.

- Lefanu, Sarah. In the Chinks of the World Machine: Feminism and Science Fiction. London: The Women’s Press, 1988.

- Lewes, Darby. Dream Revisionaries: Gender and Genre in Women’s Utopian Fiction, 1870-1920. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1995.

- Johns, Alessa. “Feminism and Utopia.” The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature. Ed. Gregory Claeys. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010. 174-199.

- Mellor, Anne K. “On Feminist Utopias.” Women’s Studies. 9 (Feb. 1982): 241-262.

- Quissell, Barbara C. “The New World That Eve Made: Feminists Utopias Written by Nineteenth-Century Women.” America as Utopia. Ed. Kenneth M. Roemer. New York: Burt Franklin and Company, 1985. 148-185.

- Suksang, Duangrudi. “Mary Griffith’s Pioneering Vision: Three Hundred Years Hence.” Utopian Visions 11, no. 1 (2000): 22-37.